When Our Waste Outlives Us:

Lessons for Tackling the Global Waste Crisis

“Waste falls on the margins and on the marginalized”

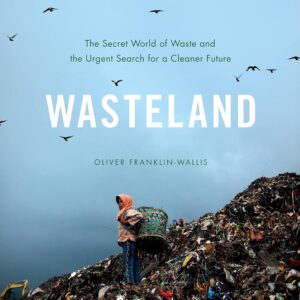

Oliver Franklin-Wallis, author of Wasteland: The Secret World of Waste and the Urgent Search for a Cleaner Future

In his book and in his conversation with Sustainable Packaging Coalition Director Olga Kachook at SPC Impact, Franklin-Wallis calls for a transformation of our relationship with consumption, recycling, and waste. Having traveled the globe—from MRFs in the United Kingdom to recycled clothing markets in Ghana—in Wasteland, Franklin-Wallis sheds light on the environmental and social consequences of our current waste crisis.

But what can we as the Sustainable Packaging Coalition learn from his research?

With members spanning brands, manufacturers, and more, we know that the people at the heart of the SPC community can make a difference. Our members hold some of the greatest levers for change to advance better outcomes for the products and packaging we produce. We’re experts at packaging, design, recovery, branding, and more—and Franklin-Wallis is an expert on waste.

From Franklin-Wallis, we can learn about the case for systems change—the intersections between packaging, our environment, and social injustice. And we can also learn about three paths forward, through:

- Standardization—cutting back on types and layering of materials in packaging

- Transparency—being clear about our materials used, our goals, and our shortcomings

- And reduced consumption—designing better products, built to last

Through these avenues of change, we can move toward minimizing waste and its consequences for our global community.

The Case for Change

Environmental Repercussions

“This is how our waste outlives us: as the places we remake, hills of garbage, hills of chat, tailings ponds. Waste … will outline even the hundred- and thousand-year timescale of landfills, so that in some distant future, if some cosmic force or tectonic break were to slice open this Earth like a birthday cake, the layers would be irrevocably altered by our presence.”

Franklin-Wallis, (p. 243)

It’s no secret that our planet is struggling to keep pace with the waste we produce. The water we drink, the air we breathe, the land we walk on has grown increasingly contaminated by waste. Take landfills, for example. Once viewed as a temporary fix, landfills actually pose greater environmental threats with age, “Over time, they erode, until inevitably they spill their contents.”

And as Franklin-Wallis writes, “We are starting to realize that some things can’t just be washed away” (p. 243).

In our land and water, toxic substances like PFAS are leaching into our soil and streams. In regards to climate, landfills are the third largest cause of methane emissions in the U.S. And the practice of burning waste releases a noxious cocktail of pollutants into the air we breathe. As Franklin-Wallis writes, much of this waste—in the form of microplastics, contaminated soil, PFAS, and more—and the environmental repercussions that follow can long outlive us.

Social Injustices

Of course, the environmental repercussions of our waste crisis aren’t felt equally. As Franklin-Wallis points out, in low-income countries 93% of waste ends up dumped while high-income countries only dump 2% of waste (p. 40).

To give shape to the connection between social injustice and our waste crisis, Franklin-Wallis calls back to colonialism. In Ghana, he writes about how fast fashion has disrupted local clothing production, filled markets, and flooded landfills. As he surveys the spaces where Western textiles disrupt Ghana’s economy and waste collection, he writes:

“It is not so much waste colonialism, as just old-fashioned colonialism: the co-option of others’ land and livelihoods for our personal gain”

Franklin-Wallis, (p. 138)

The waste crisis disproportionately impacts low-income and marginalized communities—we see it in Ghana, in Malaysia, in China. But perhaps nowhere is as stark as the Ghazipur landfill in India, where a booming informal waste market relies on waste pickers. People, often from impoverished backgrounds, climb a 14 million metric ton mountain of trash that reaches heights of 71 yards. Every day, waste pickers risk their safety, sifting through towers of sometimes toxic trash on this “mountain” that can reach temperatures up to 122°F (50°C).

A waste picker in Ghazipur is featured on the cover of Wasteland.

The Ghazipur landfill is a stark reminder that waste shipped to other countries doesn’t disappear—it just becomes someone else’s problem. And locally, landfilling or recycling that waste in facilities next to marginalized communities exacerbates the social injustice of waste, too. We saw that clearly in New Orleans, where fence-line community advocate Jo Banner shared her experience from the frontlines of “Cancer Alley.”

To meet the needs of our changing climate and to right the wrongs inflicted on our marginalized neighbors, we looked to Franklin-Wallis’ research not just to identify the problems in the system, but to see new paths forward.

A Path Forward

Standardization

At SPC Impact, Director Olga Kachook posed the question: Could the solution be as straightforward as standardization?

While the average consumer might understand packaging and recycling basics, packaging with multilayered films or multi-material components aren’t as straightforward.

One avenue for addressing the global waste crisis, according to Franklin-Wallis, is as simple as standardizing. In Wasteland, he quotes Chris Hanlon, Biffa Polymers’ commercial director:

“If we really want to fix plastics recycling, we should scrap the labels and the International Resin Code. There should probably be three or four categories—so get rid of everything else. Get rid of multilayered films, multi-material packaging. Why are we still selling sandwiches in cardboard and plastic? Do it in cardboard or do it in plastic. The trick would be to make packaging standardized, like milk bottles.” (p. 72-73)

While it may seem overly simplified, there are indeed plenty of opportunities to streamline material categories and packaging formats. The “spirit of standardization,” Franklin-Wallis said at SPC Impact, can help us to address the issues of our global waste crisis far upstream of waste pickers and landfills.

If you’re interested in standardizing your packaging while also tackling single-use waste, you can get involved with our Reusable Packaging Collaborative.

Transparency

Transparency breeds trust, but right now the majority of people don’t have faith in systems as vital as recycling. To get people to participate in recycling and reusing, we know that fostering trust through transparency can help prevent waste from trickling out to marginalized communities.

Franklin-Wallis underscores the need for transparency in overhauling waste systems:

“We need a waste system that is transparent and, above all, honest … We should eradicate the misleading resin codes on plastic packets and publish actual recycling figures, not those based on guesswork and half-truths. We should stop discussing ‘plastic’ and instead talk about specific materials—HDPE and PET and LDPE—at school, teaching kids the advantages and limitations of each. Call things by their names. Waste pickers know the value of every material. Once you do, too, you’re far less likely to waste it.” (p. 330)

Transparency can take many forms. It can take the form of labeling for recyclability, like how our sister project, How2Recycle, provides brands with recyclability labels. And as brand holders, we can also set clear public goals and provide regular progress updates, learn from the successes and failures of industry peers, and educate the public on materials from an early age.

At SPC, we foster education, collaboration, and action to advance sustainability. And when we think about those values in action, we think about examples like Sam Harrington at SPC Impact presenting Danone’s “Shelf of Shame.” He showed the shelf, which holds products with recyclability issues and exists in offices to inspire better packaging, to hundreds of packaging professionals at the event.

These moments of honesty and vulnerability can lead us to the transparency we need to build trust in our work and drive better outcomes for our environment.

Buy Better—or Buy Less

Writing about the history of planned obsolescence, Franklin-Wallis quoted the Journal of Retailing from 1955:

“Our enormously productive economy demands that we make consumption our way of life… We need things consumed, burned up, worn out, replaced, and discarded at an ever increasing rate.” (p. 256)

In other words, Franklin-Wallis writes: “Waste was no longer just a side effect — it was the goal,” (p. 256).

Buying better—or for us, designing better—and buying less are part of if not the solution, according to Franklin-Wallis. To tackle the waste crisis, he writes that we can prioritize repair, reuse, and longevity to nurture a real relationship between people and the things they purchase. This philosophy can help foster consumer stewardship, move us away from the craze of disposable consumption.

At SPC Impact, Franklin-Wallis cited the benefits from a business perspective, too. “It’s easier to sell a product that’s made better,” he said.

Underpinning all these efforts lies a fundamental shift in our relationship to waste and consumption. Rather than treating waste as inevitable, Franklin-Wallis suggests we strive for a future where standardization, transparency, and better design can turn the tides in our waste crisis. Because tackling the global waste crisis will require sustained education, action, and collaboration. But together, by heeding Franklin-Wallis’s calls, we can continue toward a cleaner, healthier, more equitable, and truly sustainable future.

By: MK Moore, Communications, Content & Design Manager