As delegates prepare to head to Nairobi for the third session of the International Negotiating Committee (INC), which is tasked with creating an International Legally Binding Instrument to address Plastic Pollution, it’s an opportune moment to reflect on the progress made so far. The INC has just introduced a Zero Draft for discussion at INC-3, which outlines various control measures related to the instrument’s objectives, offering one, two, or three options for each. This article delves into the implications of these options and their potential impact on the fight against plastic pollution.

Among the control measures presented in the Zero Draft, two measures have three options, eight have two, and nine have just one. While it’s still early in the process, given the timeline set for developing the instrument, decisions may need to be made swiftly. However, certain procedural matters, like voting rules, could still pose challenges.

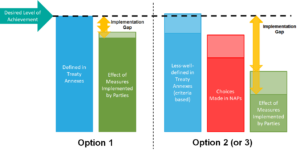

So, what can we infer from the Zero Draft and the options it presents? Most of the Control Measures that might (as per the Zero Draft) require Parties to take meaningful actions have more than one Option proposed. In these cases, Option 1 would, in conjunction with associated Annexes, prescribe targets and outcomes that Parties had to meet. The Option 2 (or Option 3 in the case of those Measures where 3 Options are proposed) variant leaves matters more open for Parties to set their own course: the Annexes would set out criteria against which they make their own assessment as to what they commit to in National Action Plans (NAPs).

Stylised Representation of Implementation Gaps Under an Option 1 and an Option 2/3 Instrument

The difference between an ‘Option 1’ Instrument, and an Option 2 is potentially profound. Of course, the extent of ambition of Option 1, or the nature of criteria used under Option 2, could affect outcomes, but the Options seem more likely to tease out which UN Members are, and which are not, comfortable with targets and obligations being set within the Instrument.

Drawing from personal experience, particularly in waste management planning, it seems reasonable to assume that there may be an implementation gap. The concern here is that the instrument’s objectives might be compromised if, in addition to such a gap between ‘intent’ and ‘achievement’, the ambition underpinning the intent is also uncertain. Opting for Option 2 (or 3, where relevant) as the basis for the agreed measures could lead to several challenges:

- Creating a significant administrative burden for Parties lacking institutional capacity.

- Heavy reliance on the content of NAPs and measures implemented by Parties, leading to uncertain outcomes.

- Consequent uncertainty in financing needs for implementing the Instrument.

- Delayed effectiveness, especially in the initial rounds of NAPs.

- Prolonged development time due to the duration for assessment and revision of NAPs, and the measures proposed therein.

- Increasing questions regarding the credibility of the Instrument.

Of particular concern to businesses is the prospect of Parties implementing a patchwork of bans, regulations, restrictions, targets, and design measures, based on their own assessments against the criteria in relevant Annexes. The lack of harmonization across these measures could result in a significant compliance challenge for businesses selling plastics and plastic products in various markets.

The Zero Draft is divided into Control Measures in Part II, Financing in Part III, and Action Plans in Part IV. Opting for an Option 1 instrument is likely to reduce the burden of preparing NAPs and their required content.

As important, there is a need to enable discussions on Part II (control measures) and Part III (financing) to occur concurrently, aligning the two areas for a more cohesive approach. For example, extended producer responsibility, as discussed in Part III, can be considered a source of funding for quality end-of-life management, which is covered in Part II. Similarly, if the intent is to reduce primary plastic production (Part II), a global plastic pollution fee (Part III) or an alternative economic instrument could be a driving force. Part II also addresses cleaning up hotspots, but it doesn’t establish a clear link to the necessary financing.

These crucial links might be overlooked if contact groups discuss financing and control measures independently, or in parallel, as they did in Paris, and are set to do in Nairobi. A coordinated effort that considers that control measures may also be financing measures, and vice versa, is essential to achieving the Instrument’s objectives effectively and efficiently.

In summary, an Instrument heavily reliant on ‘Option 2 (and 3)’ type measures leaves too much to chance to make a significant impact within the desired timeframe. We strongly urge delegates to consider developing an ‘Option 1’ style instrument, which would offer some harmonization across measures implemented by Parties, aiding businesses in formulating their strategies. This approach also ensures that well-designed measures can provide the requisite financing, an opportunity that should not be missed in the fight against plastic pollution.

Dr Dominic Hogg of Equanimator is working alongside Reloop, an international non-profit organisation leading on the development of a circular economy – see www.reloopplatform.org.